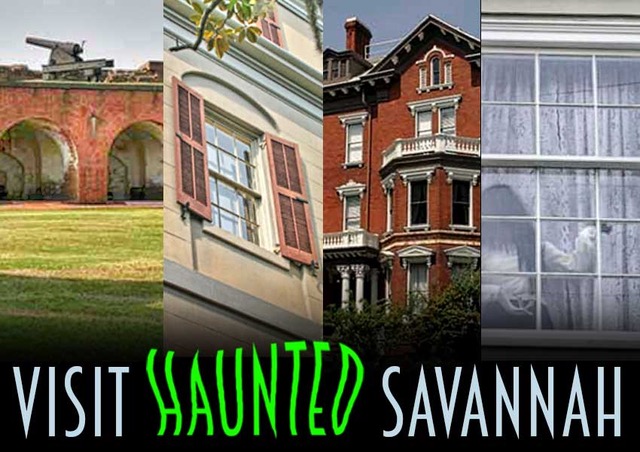

Savannah Georgia

Fort Pulaski

Restless spirits of some of the poorly treated POWs are still in captivity.

A spirit of a Conferderate officer appeared as a solid, life-like figure by an environmental trigger.

Both Union and Confederate soldiers in spirit form are still on duty here.

DESCRIPTION

This 1830-1847 era military fort can be described as an old school “masonry fortification,” which used 25,000,000 bricks in its five walls. Each wall was seven to 11 feet thick and 32 feet high. It was originally built to include “67 arched casemates,” for housing soldiers and storing supplies. These casemates acted as a firm foundation for supporting a “30 foot wide terreplein” where the cannon platforms were placed. Fort Pulaski was solidly planned and built to last through any assault, natural or manmade. Its near-perfect condition testifies to its enduring qualities “despite having borne the brunt of numerous powerful hurricanes and one unrelenting bombardment.”

When Tom and I visited, awe found it to be n impressive structure, wvery much in the category of “mother of all brick fortresses,” complete with a moat and drawbridges. Alligators and perhaps other beasties seem to enjoy the moat, so don’t go swimming!! We saw the graves of Confederate soldiers, who died here because of the poor living conditions and punitive starvation diet they suffered while imprisoned.

There is also a museum on site, with informative signs for visitors taking the self tours.

HISTORY

After the War of 1812, when the British were able to sail up the Potomac River and burn the White House, it became real clear that a coastal defense system was needed. The federal government thought, “Wouldn’t it be grand to have a fort on Cockspur Island?” They took control of 150 acres from a private party, and originally planned to build a two story fort with three tiers of guns, but there was a fly in the ointment.

The land marsh and soft mud, which provided a challenge for the Army Corp. of Engineers. Foundation pilings were driven 70 feet down to firmer ground. These pilings proved to be a firm foundation which could support a one story fort, which worked out well.

Fort Pulaski was finished by 1847, but only two men were stationed there, and it wasn’t really equipped or used as a serious facility. By 1860, only 20 of the planned 146 guns were actually in place, ready for use. So, it is not surprising that it was a cake walk for 134 Savannah Confederate Volunteer Guards and Chatham Artillery soldiers to take over the fort, just before Georgia left the Union and joined the Confederacy. The fort was in rebel hands for over a year.

The cagey Union forces, led by Union Brigadier General Quincy Adams Gilmore, snuck over to Tybee Island and secretly built 11 battery units, armed with a new weapon: rifled cannons and mortars. The Union attack featured 5,275 shots from cannons, which shot more accurately and with a lot more force, eliminating the need for risky attacks from boats with the old fashioned cannons.

Fort Pulaski’s defenses were no match for this type of new weapon. When one of the fort’s walls was badly damaged, leaving a clear hole dangerously close to the ammo storage area, Confederate Col. Charles Olmstead saw the writing on the wall: death and destruction. He surrendered the fort, which may have been a wise move, but it also haunted Olmstead the rest of his days and perhaps his eternal rest, too.

Union forces repaired the damage, and whipped the Fort back into shape from June 1862 — May 1863. By 1864, Fort Pulaski was a secure place for ammo storage and keeping Confederate prisoners. In 1864, 592 of the original Confederate prisoners from Fort Delaware, known as the “Immortal 600” who became political pawns in the battle of Charleston, arrived at Fort Pulaski, where they received poor treatment as revenge and retaliation for the South’s mistreatment of Union prisoners.

After the war, Union General Gillmore returned to Fort Pulaski to modernize it so that it wouldn’t be easy prey for another rifled cannon attack. Most of the improvements were made in the demilune area of the drawbridges, which were outside the main fort. However, the powers that be lost interest or lost funding, and the planned changes for the main fortress were abandoned. Finally, 15 years after the end of the Civil War, Fort Pulaski was decommissioned as a military facility, though it was still owned by the War Department. It was abandoned until 1898, when American troops briefly moved in during the Spanish-American War. After that conflict was settled, the fort once again was left to the elements and time, forgotten and abandoned.

After World War 1, interest in preserving places of history prevailed and Fort Pulaski, now in deplorable shape, its graveyards buried, was chosen for restoration. “On October 15, 1924, using the authority provided by the American Antiquities Act of 1906, President Calvin Coolidge established Fort Pulaski National Monument. The property was transferred from the War Department to the Department of the Interior on July 28, 1933. The National Park Service’s new mission was to oversee the restoration, management, and protection of this monument, thanks to the funding provided to do so.

It wasn’t until 1998 and 1999, that the cemetery sections were found via old documents and through modern archeology. Confederate, Union, and post Civil War burials were identified. Archeology focusing on the Immortal 600 and other burials at Fort Pulaski was one of the priorities of the 1998 and 1999 field seasons.

HISTORY OF MANIFESTATIONS

There was no plan or agreement on the treatment of captured prisoners during the Civil War. They were put in dangerous situations, used like hostages, abused and mistreated and generally seen as political pawns. As no prisoner exchanges were encouraged during the Civil War, prisoner overcrowding was common in both Union and Southern prisons. Southern prisons such as Andersonville had the added problem of not having enough food to feed their prisoners because of Union port blockades. News of this awful situation leaked out to people in the North, and the urge to retaliate mounted.

The city of Charleston stubbornly put up a great fight defending itself against the Union, which in turn led to constant bombing by Union forces. To try to get relief, General Jones, under pressure from Confederate leaders, brought in 600 Union soldier prisoners within the city limits, putting them in harm’s way, which was becoming the Southern strategy. Union General Foster, responded by taking 600 Confederate prisoners (the “Immortal 600”) from Fort Delaware to the beaches on Morris Island, South Carolina, placing them in front of Union batteries, where 80 of these prisoners died on the beach.

This deplorable use of POWs ended somewhat when Yellow Fever erupted in Charleston, and 600 Union soldier POWs were moved outside the city. The surviving Confederate soldiers were taken to Fort Pulaski into abusive conditions, and put on a starvation diet by order of General Foster, as payback for the lack of food given to Union soldiers in Southern POW camps. The surviving 520 suffered and endured in the unheated casemates from October 1864 — January 1865. They kept themselves alive by eating rats, cats and kittens. By the end of February, conditions improved a little after 33 prisoners died from this abuse. Finally, on March 5th, 1865, the remaining prisoners were shipped back to Fort Delaware, except for four prisoners who were too weak to move, and wound up dying there.

Forty-four of the 520 prisoners died from the lack of basic necessities and food, and never got justice for the mistreatment they suffered. Some were buried in unmarked graves.

Something stopped this awful treatment. Perhaps the Union Army realized what they did was wrong, and stopped the abuse after only four months. Perhaps they didn’t want to fuel the hatred of the Confederacy. Calmer, saner minds took the helm, but not before men died, leaving Fort Pulaski with a stigma as a place of suffering and abuse. Many of its prisoners suffered health problems the rest of their lives.

The Union soldiers who had to carry out the orders of General Foster were also traumatized on some level. Seeing fellow Americans freezing, becoming ill and slowly wasting away from lack of food would affect anyone with a conscience.

The 30 hour attack on Fort Pulaski did kill some Confederate soldiers, as all battles bring fatalities.

MANIFESTATIONS

Unknown Union and Confederate soldier entities

have been seen still on duty around the fort, and outside on the surrounding grounds.

An unseen presence has been felt standing near the living, calling the person’s name.

Feeling of sickness, fear, despair and misery come over sensitive people in certain parts of Fort Pulaski.

Orbs have been captured on film.

In the 1980s the film GLORY was shot in Savannah. A group of Confederate soldier extras, dressed in their uniforms, decided to visit Fort Pulaski on the way to the set. Imagine their surprise when a Confederate Lieutenant approached them, and reprimanded them for not saluting him. He ordered them to fall into line because a Union attack could happen at any time, which they did as to go along with this improvement and put on a show for the other visitors. This officer then gave the order to face about, then vanished into thin air.

STILL HAUNTED?

Yes indeed.

Many restless souls of soldiers from both sides are still on duty, while some of the dead POWs can’t rest and perhaps are reliving their abuse, not realizing that they have been freed.

LOCATION

East of Savannah, Fort Pulaski can be found on the claw-shaped Cockspur Island at a point where it guards the mouth of the Savannah River, just a mile away from Tybee Island.

From I-95, take exit for I-16 about 15 miles west of Savannah. From I-16, take U.S. Highway 80 East. Follow signs for Fort Pulaski, Tybee Island and beaches. The Fort Pulaski National Monument entrance is approximately 15 miles east of Savannah. The Fort is 5,623 acres in size.

SOURCES INCLUDE

- militaryghosts.com

- cr.nps.gov

- ghostvillage.com

- Haunted Holidays

Edited by Laura Foreman pg. 147

Discovery Communications, Inc. – 1999 - Haunted Savannah, The Official Guidebook to Savannah Haunted History Tour

by James Caskey pg. 191-194

Bonaventure Books – 2006

Our Haunted Paranormal Stories are Written by Julie Carr

Our Photos are copyrighted by Tom Carr

Visit the memorable… Milwaukee Haunted Hotel

Your Paranormal Road Trip